Pat Littlejohn Interview

Dave Pickford, Editor of CLIMB magazine, spoke to Pat Littlejohn in October 2012. Read the full interview here.

Can you remember the first route you ever climbed?

Yes, it was Barn Owl Crack at Chudleigh Rocks (though we didn’t know that at the time). I was with my childhood friend Jeff Jones, both of us 14 years old. We had an 80-foot hemp rope nicked from Exeter Flower Show, one piton which we’d bought from Grays of Exeter, and a hammer from my Dad’s toolbox. We just tried what seemed to be the easiest way up the cliff. Half way up we managed to hammer in the piton. We had to untie to thread the rope through the eye of the piton. After that we tried another climb and got a bit stuck, and that was when we were spotted by some members of the Exeter Climbing Club who invited us to join up and learn to do things properly.

Can you describe the gear were you were using back then?

Once we’d joined the club we could use laid nylon ropes and rope slings with steel karabiners. Nuts were just coming in (1965) so we soon had nylon slings of various widths threaded with everything from tiny nuts from my Meccano set to huge wheel nuts scrounged from the local bus station. Initially I just climbed in old school clothes and shoes that were too scruffy to wear to school. They were semi ‘winkle-pickers’ which wasn’t ideal but at least they had black carbon rubber soles which seemed to grip OK. I climbed up to VS in these before getting a pair of Hawkin’s ‘Masters’ – the rock shoe reputedly designed and worn by Joe Brown. After 6 months (while still 14) I led my first XS – Oesophagus at Chudleigh (now thankfully restored to E1 after being downgraded to HVS for many years!).

Back then when you started out in the 1960s, the old ethic of ‘the leader never falls’ was very much the status quo. Can you remember the first proper lead fall you took?

Absolutely – it’s one of the most memorable experiences of my life! I was while trying the first ascent of The Bilk at Avon Gorge, in 1969. I’d arranged to climb with Graham Skerratt but he turned up hours late without any climbing gear, intending to call the day off. I was so psyched up about the line I persuaded him to climb anyway so we split my gear. I ended up with the rock shoes but with just a single 9mm rope tied around my waist. At the final wall I was trying to place a peg runner when the handhold I was using broke in half. I couldn’t reverse or place any protection so I just hung there for an agonising 10 minutes while every bit of strength drained away. I was convinced that if I fell the rope would either break or cut me in half! Eventually my fingers unpeeled and I took a 45-foot plummet into space. Graham took off from the stance and ended up dangling beside me. After that it was many years before I took another leader fall.

When you were just 16 you made the first ascent of one of the best HVS’s in the UK, Moonraker at Berry Head in Devon. Did that formative experience drive you to seek out new lines rather than repeat existing ones?

I was already hooked on the excitement of doing first ascents having climbed about a dozen behind Frank Cannings and Pete Biven in the summer of 1967 and several with other climbing mates like Steve Jones, John Hammond and Steve Dawson. But Moonraker was in a different league, bigger and more committing than anything I’d done before, and on such an awe-inspiring cliff! Pete soon referred to it as a route of ‘national importance’ and began repeating it with well-known climbers like Ian Howell, Rustie Baillie, John Cleare and Al Alvarez. Later that summer I made the second ascent of Barbican on the same crag (with Frank, a week after he’d done the first ascent). This was another amazing climb which showed the potential for SW sea cliffs to produce routes equal to just about anything else being done on British sea cliffs. There was so much coastline still to explore so those were very exciting times.

You’ve been one of the most prolific explorers in the history of British climbing. Briefly, can you describe what it is about doing first ascents that so fascinates you?

I guess you gravitate to the type of climbing you find most inspiring and satisfying, and also to the type which is most valued by the climbing fraternity at the time - which for most of my career has been hard first ascents. Also you tend to do what you excel at. I’ve never been that bothered about trying to push the limits of difficulty - what really motivates me (and still does though I’ve entered my sixties) is climbing a high quality line in good style. So if I get myself fit enough and good enough to do that, I’m happy. I guess I’m lucky in that the urge to explore in me has been nearly as strong as the urge to climb, so I’m never short of really good projects to maintain enthusiasm.

Is making a first ascent a more creative experience than repeating an existing climb?

You can’t compare it to a truly creative act like producing a painting or a novel, but yes there is some element of creativity in making a first ascent. For a start there has to be some vision, some recognition of potential which not everybody sees or is capable of realizing. Some climbers are technically brilliant but without the vision to make significant first ascents; others have vision which far outstrips their climbing ability (and then you get into real problems, e.g. Maestri on Cerro Torre just to give an example safely far away from home!). Each new trad climb is unique - you bring it into existence, name it, describe it then release it to the world where it may be lauded or panned, a bit like how a new play is judged by the critics! Pearson’s Walk of Life is a perfect recent example of this process at work!

The sea cliffs of south west England were your major hunting ground for new routes right through the 70s and 80s, and you established many of the region’s finest hard classics. What is it about sea cliffs in general, and south west England in particular, that inspire you as a climber?

Sea cliffs were a great new frontier for British climbing which gave us a vast amount of virgin rock to go at and a distinctly different climbing experience. I’d always loved the Devon & Cornwall coast having been raised down there, which is maybe why I developed a special affinity for sea cliff climbing. I like the greater commitment involved (as you often can’t retreat), the extra dimension of the sea with its changing moods, and also the feeling of isolation and remoteness that you can experience even when the cliff is near a busy resort like Torquay. To sum it up I guess there is a more powerful sense of adventure on sea cliffs than you can find on inland crags in the UK. Nowadays what I appreciate is the amazing variety of climbing areas around the coast of the SW and Wales, and also the sheer beauty and richness of the coastal environment. (Continued...)

I couldn’t reverse or place any protection so I just hung there for an agonizing 10 minutes while every bit of strength drained away. I was convinced that if I fell the rope would either break or cut me in half!

After your close friend and regular climbing partner Keith Darbyshire died in a fall whilst exploring Nare Head in Cornwall, you didn’t make any first ascents in the south west for a number of years. In what way did Keith’s untimely death affect your climbing?

For a time I was very nervous in the sea cliff environment, not so much for myself but for others. I’d see someone scrambling down to a climb and have a panic attack! What got me over it was a long climbing trip to the States, but it was 37 years before I could bring myself to climb at Nare Head again. Dave Garner and I had a great day there this spring climbing two new routes, and I now realize that the problem was not with the place but with that particular tragic day and its circumstances. You never forget someone like Keith and it still feels like I do some of my climbing for him, maybe a line that we’d looked at or climbing somewhere that we’d started to explore or just talked about. Amazingly enough, quite a few of the climbing projects Keith and I contemplated in the early 70’s still haven’t been done. Some are pretty insane but there are others that I’d like to have the time and strength to complete.

Alongside your passion for exploratory rock climbing, you’re also one of the leading alpinists of your generation. Do you see alpinism as a separate activity to rock climbing, or a natural extension of it?

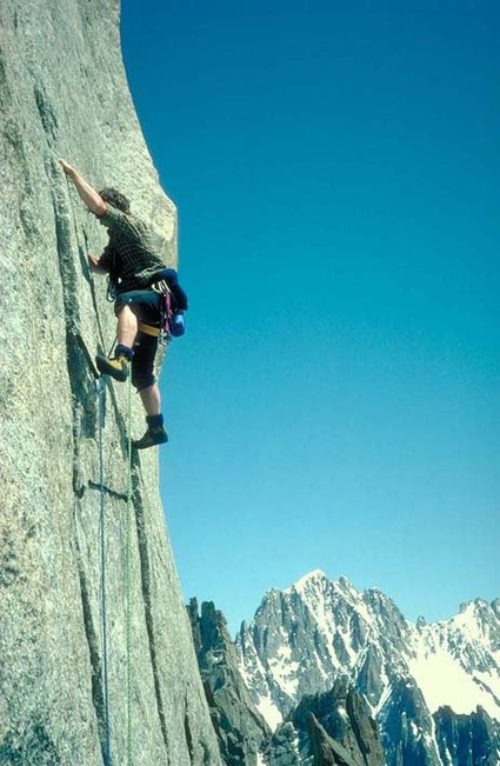

I don’t know about leading alpinist but I‘ve had my moments, particularly on alpine rock through the seventies when Steve Jones and I were probably the fastest team around and I was trying to introduce a ‘clean climbing’ ethic to big alpine faces (to reflect what was happening in the US and UK). In 1971 we did the American Direct on the Dru with 2 points of aid. I was climbing in a pair of oversize rock shoes and carrying mountain boots. A member of the Alpine Club later accused me of cheating because I wasn’t climbing in the boots! We did quite a bit over the next decade, building up to the S Face of the Aiguille du Fou with 1 point of aid. This was possibly E6 6b UK grade. For all I know these routes are now equipped but they were virtually free of fixed gear at the time. As we know Alpine rock climbing took a very different direction, but for me Alpinism has definitely been an extension of the skills and adventure I look for in rock climbing. Even if you do all your climbing on bolts you can find equipped routes in the Alps which give a much bigger challenge than you find on sport crags, so although the link may have weakened with regard to mixed climbing it is definitely still there on rock.

When was your first trip to the Himalaya, and what did you climb?

In 1984, to try the E Face of Kedar Dome with Cubby Cuthbertson, Martin Moran and John Mothersele. We had big problems – first Cubby got pneumonia and had to be evacuated, then Martin’s wife Joy got ill and Martin had to escort her to back to Delhi. In the end John and I made an alpine-style push on the W Ridge of Karchakund, which had been previously been climbed siege style by an Austrian team. We climbed all the difficult ground but had to turn back 250m below the summit because of mis-timing our summit day.

Now from mountains back to the rock. Despite your passion for trad adventure climbing, do you ever go sport climbing or bouldering?

I can take a couple of days of sport climbing then I question how I’m spending my time. It’s all too similar to going to a climbing wall, especially single pitch sport climbing. Steve Sustad and I went to Kalymnos last year and spent most of our time putting up trad routes! Having said all that I’m sure my climbing fitness would benefit from a sport climbing holiday each year, it just never quite makes it to the top of the priority list. Bouldering is a different matter though – I do it to get fit (along with sea level traversing) and have always enjoyed it.

You’ve been highly critical of Petzl’s ‘Roc Trips’ in the past. Why?

I’m a big fan of Petzl products (I use a Petzl harness for a start!) but I was a bit shocked by the report of the trip to China last year when they bolted several hundred routes, cleared the crag bases of vegetation and created lots of new trails, all in an area supposed to be a protected National Park. It sounds like they are currently doing something similar in Argentina. To me the creation of these ‘sport climbing resorts’ is completely at odds with the sort of low-impact exploration we’ve been exhorted to do in the mountains for the past four decades – i.e. a ‘tread lightly’ approach leaving little or no traces. Maybe I’m being too cynical, but it seems to me that talented climbers are being used to construct huge numbers of bolted climbs with the clear objective of expanding the market for Petzl products in the emerging economies. Also to promote the Petzl brand through the climbing media (which is only too ready to report glowingly and uncritically of these trips – Petzl are big advertisers after all). I care a lot about the image that climbing has in the world because I think it will ultimately affect our right to access. As sport which does no damage and leaves few traces we can reasonably expect access to any cliff or mountain area, but if climbing is increasingly seen as a sport which involves teams of people with power drills and which requires cleared trails and cliff bases for convenient belaying, I can see why people wouldn’t welcome climbing, particularly those in charge of special landscapes like National Parks.

Do you think bolting a line that could be climbed on trad is an act of vandalism? If so, why?

Not necessarily, but what I do believe very strongly is that bolting worldwide should be contained in much the same way as it is contained in Britain, Norway and much of the US. In some countries now, ‘natural’ rock is a thing of the past – it has all been artificially modified to facilitate sport climbing. In my view cliffs and mountain faces are as much part of the natural environment as any other part of the landscape, and as climbers we simply don’t have the right to cover them in metal fixtures for our own convenience.

Was Maestri’s Compressor Route on Cerro Torre the greatest act of vandalism in the history of climbing?

Maybe the greatest single act of vandalism, but many people who condemn it seem quite relaxed about the thousands of bolts being placed each year by climbers in other wild places around the world. The worrying thing to me is not the bolting of individual routes but the relentless bolting of more and more natural rock to facilitate this relatively bland form of rock climbing.

In my view cliffs and mountain faces are as much part of the natural environment as any other part of the landscape, and as climbers we simply don’t have the right to cover them in metal fixtures for our own convenience.

Do you think the recent boom in sport climbing has made the culture of rock climbing as a whole less adventurous?

For adventure you have to have risk, and the whole point of sport climbing is to eliminate the risk and focus on the athleticism. Many fantastic bold ascents are being made alongside the boom in sport climbing, sometimes by climbers who sport-climb to improve their skills. But in many countries nowadays rock climbing equals sport climbing, so it’s essentially risk free and feels entirely different to the sport I’ve been pursuing for most of my life.

In my view, sport climbing can be as adventurous as trad climbing – particularly on steep, hard multipitch routes on cliffs like Sardinia’s amazing Gole di Giruppe or Morocco’s Taghia region, or on many other recent discoveries in Mexico, China, Brazil, and elsewhere. What is your view of this concept of ‘adventure sport climbing’ as whole?

Adventure is a hard concept to define, and I’m sure that multi-pitch sport routes that are climbed ground-up feel pretty adventurous. But basically the man with the drill is in control; he can make the route as safe or as bold as he chooses. I find the phrase ‘adventure sport climbing’ a bit pernicious, like ‘minimalist bolting’. Does it mean that the bolts are just a bit further apart? Truly adventurous sports deal with an element that is bigger than you are and which ultimately calls the shots. In surfing it is the sea. In climbing it should be the rock that dictates to us, determining not just how difficult the climbing is but how serious it is also. With a drill you can place protection anywhere. If you really want adventure leave the bolts behind and try to tackle these crags with a trad rack.

With the massive explosion in the sport climbing and bouldering demographic as a result of the proliferation of climbing walls, how can all these talented young climbers who don’t know what cams or wires are for be introduced to trad climbing?

Well the first thing is to ensure that there is always an arena for trad climbing – this is fast vanishing in many parts of the world as natural rock is consumed by bolting. Many climbing wall and bouldering stars will never take up trad climbing and maybe that doesn’t matter, but trad climbing has to be vigorously defended for people that want to pursue a more adventurous sport. Climbing and mountaineering have always been among the ultimate outlets for people seeking an adventurous sport/lifestyle, and we have to make sure that the sport continues to attract these people; otherwise it will very soon become an over-safe, organized and regulated sport just like any other.

Doug Scott once suggested that the BMC should ‘fund bolt removal’, in a bizarre statement which came close to suggesting the annihilation of all sport climbing in the UK. What’s your view of this extreme position?

Poor Doug – this statement is always taken out of context and misinterpreted! He was saying that just as the BMC funds bolt replacement on cliffs where it has been agreed that bolting is acceptable, so it should also fund bolt removal/repair of the rock where bolts have been placed in breach of bolting agreements brokered by the BMC. I don’t find this position extreme – I think most British climbers would agree with it and in fact it is pretty much BMC policy (and I believe it’s being implemented in Western Cornwall right now). Doug is definitely not advocating the annihilation of sport climbing, but like me he believes that it should be contained, and that around the world each country should carefully consider what rock should remain natural and what may be appropriate for bolting. This is what he has been working towards at the U.I.A.A. and unless something like this happens, there is a real danger that just about all accessible rock will have been bolted by climbers in the foreseeable future. This to my mind would be a disgrace for the sport and an environmental crime.

Do you find it hard to accept the fact that the best trad adventure climbers of the present day - guys like Nico Favresse and Alex Honnold - are also accomplished sport climbers, and sport climbing has now become an essential tool for high level trad climbing?

Not at all, but to get the benefits of sport climbing it is not necessary to keep bolting up more and more rock. Countries like France and Switzerland have a huge surfeit of bolted climbing such that many bolted cliffs are now completely neglected (but still covered in redundant metalwork placed by climbers). You now have to search quite hard to find any trad climbing and even harder to find any information about it! In Britain, although we are seen internationally as ‘anti-bolt’ we have enough sport climbing venues to challenge and train our best trad climbers if that’s what they choose to do, and I personally think we have the balance about right.

What are your five favourite crags in Britain?

For doing established routes probably Bosigran/Great Zawn, Lower Sharpnose Point, any Torbay crag, Cloggy and the Llanberis Pass.

What are your five favourite places around the world for exploratory trad climbing?

Currently North Cornwall, South Cornwall, Kenya, Ethiopia and the Son Kul canyons of Kyrgyzstan.

What’s the best place in world right now for accessible exploratory alpinism?

Not sure, but I’m into the Tien Shan myself and that will have plenty to explore for the next ten years at least.

What’s the best new route you’ve ever done?

Sticking to rock climbs, in Britain it would be a toss-up between Il Duce in N Cornwall and Above and Beyond at Fair Head. Internationally it would be Dark Safari (600m E6) on the N Face of Poi in northern Kenya.

What’s been the most satisfying experience of your climbing life?

The first time I felt utterly satisfied with climbing was after the N Wall of the Eiger in 1979. I had no urge to climb for a couple of months – a record! The NE Pillar of Taweche in Nepal was just as satisfying and also left me with numb swollen toes that couldn’t bear rock shoes for 2 months!

Finally, what would you take with you to a desert island?

Mask, snorkel and really comfy rock shoes.

Related News Articles

ISM Virgin Peaks Expedition 2024 - Tien Shan Kyrgyzstan

ISM trip report of our trip into a very remote part of the Tien Shan Mountains, Kyrgyzstan

Read Article

Getting Into & Developing Your Climbing

Indoor bouldering is a great place to start if you want to try climbing for the first time. You can…

Read Article

ISM Virgin Peaks Expedition 2023 – Tien Shan Kyrgyzstan

ISM trip report of our trip into a very remote part of the Tien Shan Mountains, Kyrgyzstan.

Read Article

Kyrgyzstan Faces 2022

This year ISM celebrated 25yrs of expedition climbing in Kyrgyzstan, with a fantastic trip to the Fergana Range in the…

Read Article